Pricing an Assignment? Begin With the End in Mind

The fees you charge your clients should not be set based on the scope of work, but rather the scope of value. In professional services, you’re not selling your ability to do, but rather your ability to solve — your head, not your hands.

Every time your client asks, “What is the fee,” your job is to bring the discussion back to the question, “What is the goal?’ It’s certainly reasonable for buyers of professional services to want to know the price of an engagement — and every client deserves a clear upfront price — but this information is almost always provided prematurely.

Many professional firms, especially ad agencies, are in the unfortunate habit of pricing client-supplied statements of work based on estimated resource requirements instead of probing for the objective the work is intended to achieve. You should be pricing the value of the hole, not the cost of the drill.

Brilliance and knowledge work

Such was the approach of Charles Steinmetz, a German immigrant to America in 1888. Steinmetz was a brilliant engineer who ran in circles that included Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla. The industrialist Henry Ford recruited Steinmetz to solve a problem Ford was having with a particular kind of generator used at Ford’s famous River Rouge plant. Steinmetz studied the generator for several days, musing about the problem, making careful observations, and taking detailed notes. At one point, he climbed on a ladder and used a piece of chalk to make a mark on the side of the generator. This, Steinmetz explained to a group of engineers, marked the spot where they needed to replace sixteen windings from the field coil.

When this work was done, it effectively solved the problem. As the story goes, Steinmetz then provided Ford an invoice for $10,000 — a sizable sum for the day. While Ford acknowledged that an important problem had been solved, he questioned how Steinmetz could have worked that long and hard and asked for a more detailed invoice. Steinmetz then supplied an updated bill that listed two items:

Marking chalk mark on the generator, $1

Knowing where to make the mark, $9,999

Ford paid Steinmetz his fee.

What's different about knowledge work

In knowledge work, the money we are paid is for the problems we solve, not the hours we work. In Ford’s manufacturing facility, it would have been perfectly acceptable to pay most of the laborers that way, because they were doing manual work — work that is standardized and repeatable. But knowledge work is completely different; it’s work that by definition is unique and customized. Manual workers generally perform at a similar level and this kind of talent is relatively easy to find. Knowledge workers perform at vastly different levels and the good ones are hard to find.

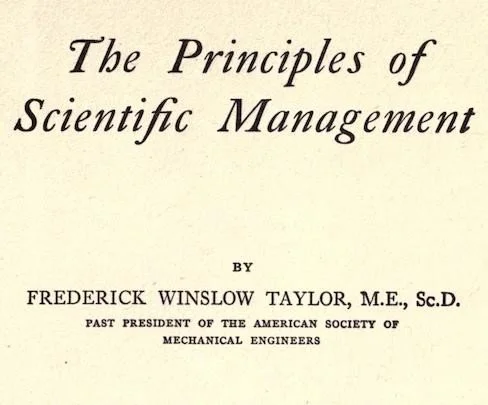

The nature of manual work was studied extensively by Frederick Taylor, and his 1911 book “The Principles of Scientific Management” became the bible of early 20th-century manufacturing. His recommendations helped improve the efficiency of assembly lines across the globe.

But a few decades later Peter Drucker helped the business community understand the concept of the “knowledge worker.” Managing a manufacturing facility requires a very different skillset from working on the assembly line. And the activities that support the successful management of a business — the kind of functions provided by professional service firms — represent knowledge work at its finest. If manual work is about efficiency, knowledge work is about effectiveness.

Solving problems instead of performing tasks

Professionals are hired to solve problems, not perform tasks. While many tasks are often required in the process (generating reports, submitting forms, performing data analysis), what the client is ultimately buying is the solution to a problem or the development of an opportunity.

So when you base your pricing on the inputs required rather than the outcomes produced, you’re almost always either underpricing or overpricing your services. If it’s an easy problem to solve, the client shouldn’t have to pay for your inefficiency, lack of organization, or inexperienced team. Charging for the time irrespective of the results is grossly unfair to the client. On the other hand, when you’re able to leverage the talent, experience, and expertise of your firm to solve a difficult problem in a short amount of time, charging for time instead of results is grossly unfair to the firm. Value creation works in both directions.

The destination, not the journey

The mistake most professionals make is jumping straight to the treatment without first making a proper diagnosis. We, and our clients, often don’t fully understand the problem and the desired result. We jump straight to the scope of work without an effective definition of the scope of value.

All of the dialog professional firms and their clients have around estimated time and required resources is largely irrelevant to the question, “What is the value to the client organization of achieving the desired objectives?” Pricing discussions should be about the destination, not the journey.